Learning, enduring ideas and other thoughts

Like drinking from a firehose.

I once heard that we lose 80% of what we learn in a classroom-type experience within one month if the knowledge isn't applied. This perhaps supports the 70:20:10 Model where emphasis is placed on learning on the job through challenging assignments (70%) compared to mentoring (20%) or formal training and qualifications (10%). However, Laszlo Bock argues in Work Rules! that there's a lack of evidence of this approach working; that to create a learning discipline and institution, teaching is the optimal way:

A learning organization starts with a recognition that all of us want to grow and to help others grow. Yet in many organizations, employees are taught and professionals do the teaching. Why not let people do both?

The common element in both views appears to be that the power of any learning experience is in the doing rather than the acquisition. In my job, I enjoy coaching and mentoring. Privately, I'm experimenting with sharing more content as a way of embedding the insights into my thinking. If nothing else, I'm forcing myself to engage with a previously unmanageable repository of articles that I've been filing away for "when I have time" which turns out to be never—unless I make it happen.

My newsletter has become the mechanism for tackling this. The "five things" series is a relatively low-effort, accessible way to maintain the discipline of regular reading, reflection and sharing. It requires creating space in the calendar for short learning-orientated sprints which has the cumulative effect of mindful, lightweight but continual growth.

Still, as I'm clearing the backlog of reading, it's like drinking from a firehose. While I don't think I can fix the volumetric issue—though I might get more efficient in capturing, organising and processing the material—I don't think that's the problem to solve. Thinking about the concept of a one-month mental "expiration date" on a large portions of what we learn, the priority appears to be the discipline of reflecting on, sharing and discussing great content.

To wit, this post—and if useful, future ones—is an effort to inculcate some of the meaningful material from the month prior. I also serves as a brief summation for anyone who might have missed the earlier posts.

Enduring ideas

Of all of the articles and citations casually curated for the newsletter recently, these are the ones that gave me pause. In one way or another, they resonated with my professional and personal experience in that period and continue to inform my thinking about people and culture.

Reimagining talent; reorienting for “spiky leaders”

Through virtually managing a team and revamping a business, leaders will find that so much of what we call “people development” is actually a set of processes that train people to manage complexity, rather than question it. Some CEOs are realizing they don’t need smooth operators—those all-rounders, devoid of obvious weakness, whose main strength is managing the complexity they often create themselves. Instead, CEOs need the messy folks who tell it like it is—those people who have “spikes,” or great strengths, in some areas and some glaring weaknesses in others. There’s magic to those diverse folks who help us find surprising ideas in surprising places. (James Allen, Bain & Company)

High-performing leaders promote trust underpinned by vulnerability

It is in how an organization treats its employees that trust is built or destroyed. Research shows that when the top management gives trust to its managers, its managers will consider this the way to act and will treat their employees in similar trusting ways. As a result, the normative behavior in place will become giving trust to each other. The activity of building trust is therefore an important leadership responsibility and one that should be exercised continuously. If accepting vulnerability and thus giving trust to others is observed as the default behavior, then it will become the norm to follow and foster all the positive effects of trust. (Knowledge@Wharton, World Economic Forum)

Haruki Murakami on dealing with criticism

That girl on the train makes me think of a jazz musician whose name was Gene Quill. He was a sax player who was famous in the nineteen-fifties and sixties. And, like any other sax player in those days, he was very influenced by Charlie Parker. One night, he was playing at a jazz club in New York and, as he was leaving the bandstand, a young man came up to him and said, “Hey, all you’re doing is playing just like Charlie Parker.” Gene said, “What?” “All you’re doing is playing like Charlie Parker.” Gene held out his alto sax, his instrument, to the guy, and said, “Here. You play just like Charlie Parker!” I think there are three points to this anecdote: one, criticizing someone is easy; two, creating something original is very hard; three, but somebody’s got to do it. I’ve been doing it for forty years; it’s my job. I think I’m just a guy who’s doing what somebody’s got to do, like cleaning gutters or collecting taxes. So, if someone is hard on me, I will hold out my instrument and say, “Here, you play it!” (The New Yorker)

Other thoughts

In between mail-outs, I've also shared other articles on LinkedIn. These were the top three popular posts for the month.

On the employee experience opportunity of lockdown

If we come out of this only focused on whether our people should be working in the office or working at home, then I think we’ve missed a big opportunity to redesign our employee experience. (Kristine Dery as quoted in MIT Sloan Management Review)

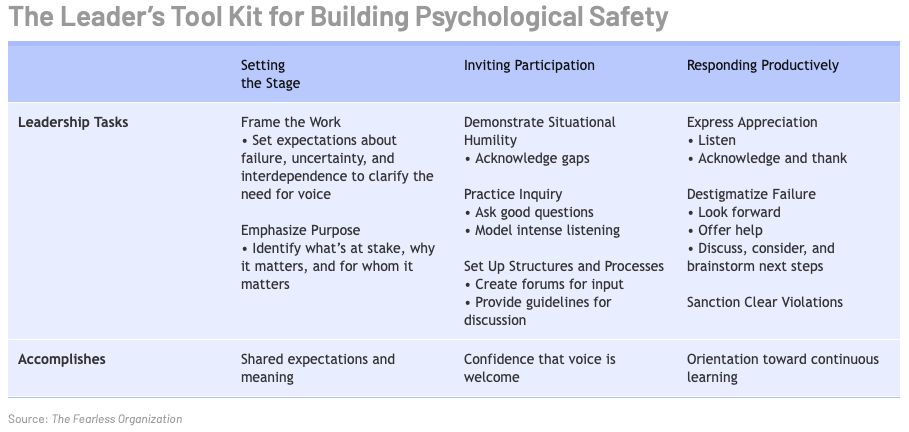

On leading fearless organisations

...leaders have two vital tasks. One, they must build psychological safety to spur learning and avoid preventable failures; two, they must set high standards and inspire and enable people to reach them. (Amy C. Edmondson, strategy+business)

The post features this practical illustration:

On reflection as a leadership discipline

Time is a precondition for slow thinking. To develop a routine, time for reflection should be a regularly scheduled and a protected event on the leader’s calendar. (Martin Reeves, Roselinde Torres and Fabien Hassan, Havard Business Review)

If you're still reading, thank you. You might be interested in my posts on work and music.