The real value of the direct-to-fan model (2013)

I was an independent musician for years before signing to a major label. With that signing, my experience changed little--much to my peers’ surprise--in that the hard work I was used to doing simply continued.

Marketing, networking, managing, administration and the sundry tasks that are entirely unmusical but necessary to the band’s operation were still my responsibility. That was fine, I anticipated what the label could reliably do for us and was otherwise happy in my work. A hands-on group, we were fundamentally interested in expanding the team around us to amplify our continued efforts. However I was under no illusions about any of this in today’s climate. I read the blogs. I followed the thought leaders. I got the right lawyer.

More surprising to my fellow local musicians was that it appeared to become increasingly difficult as a signed band. It was tougher and took longer to get things done; not even ambitious things--simple things. Long email threads, meetings and deferred responsibility. As a digital native sensitive to the band’s tech-savvy fanbase, responsiveness and transparency were things I valued highly and I found myself struggling with a multi-tiered, time-poor business partner.

I often wore the brunt of criticism on their behalf: why wasn’t our music available in lossless formats, why wasn’t it available on a platform of choice, why wasn’t it available in some territories and why — when people were just trying to help spread the word — did we serve a horrible copyright infringement notice? Didn’t we get it?

We understood every complaint emphatically and were at times equally confounded at the industry’s automated systems and rationale.

Before the band signed, we were early adopters by New Zealand standards; freemium-advocates (interestingly, that’s what got the label’s attention) who valued the kinship that gave us with fans. We couldn’t easily explain all this while signed, despite a desperate desire to, because of commercial sensitivities we had to respect.

However, I also got tremendous benefit from a major label relationship in a way that made sense to me. I had one expectation that I maintained whenever things were difficult, slow, unclear or embarrassing: an album. Beyond the terms of the agreement or any other implications during our dialogues, I knew the entire experience, for better or worse, would be worth an album I didn’t have to paid for. At least, not right now. And without interest or a personal guarantee.

That was a very personal, long-sought conclusion.

At that time, even though the business plan was terrible, any associated challenges or limitations could be rationalised. Understandably, that kind of thinking might not be an option for everyone when it comes to their art. If you are financially dependent on your music or struggle philosophically with compromising margins or control, power to you! I sought value in other experiences and am grateful for those.

Let me say that I like the people I worked with during this time. We drank beer together. For the band, this was a relationship it wanted and went into with eyes open with the best negotiated contract it could afford for who we were and what we wanted to do. I don’t dwell on what could have been done better. An album. I’m grateful.

Unlike some of my peers, I never saw one particular business relationship as “the answer” (perhaps this misconception prevails most among rock musicians). That label was crumbling around the staff when we joined. Ultimately they were fettered by uncreative role descriptions written for an old business model and later, when that broke, they sadly lost their jobs. Whereas we would continue to be a band and songwriters and always work to enable that because commercially profitable or not, music is bigger than the bounds of industry.

We make music for us. We’d like it to be heard; however, wherever. I assume people like to be able to stream or buy music from our own domain because it feels like they’re supporting us directly. They are--whether or not we have to later remit the funds to a third party.

In the wake of some of that criticism, I leveraged the negative feedback to make a case for unrestricted use of Bandcamp. It was entirely tenuous and we had to set prices inordinately high but we got the approval and from what I was told, it outperformed iTunes NZ by a staggering degree.

Given this fact and my earlier experience with the direct-to-fan model, we demonstrated the following.

Quality as a value proposition

We’re a band that deals in guitar tones, drums sounds and audio nerdistry. Bandcamp is for audiophiles. Lossless quality supports our audience's listening behaviour.

We’re a niche act with a global audience

We're part of a broadly distributed but fervent music genre and internet community. Only a fraction of that is New Zealand-based with access to iTunes NZ (or bothered to import a CD at the prices available).

So, restricting channels by territory is bad for business

The key to my argument was that it's simpler and faster than other service providers to account for every sale and territory and to direct monies to the appropriate label or distributor.

Full-song or album streaming is better product demonstration

90-second clips aren't powerful marketing tools.

Embeddable, socially-optimised players encourage sharing

Making it easier for people to share means their more inclined to actively and passively promote your music.

We must be discoverable

Whether someone pays for music or doesn’t, there is an expectation that we should at least be easily searchable.

All that is not to discount iTunes as a sales channel--I've use it. I also use Bandcamp. They’re like genres of internet consumption and can exist in the same world.

Would I work with a label again? The short answer is, yes. I fully expect there are labels today that appreciate their legacy as an industry construct, are acutely aware of the new services and thinking available and so have correctly identified their niche value proposition to artists. I would welcome a conversation around this; it interests me.

This doesn’t preclude majors. Now, I can demonstrate the value of direct-to-fan in empirical, commercial terms. Under a major label’s aegis, it was a high performing model. Surely they are in a position to enhance and exploit that.

It’s worth noting my experience the week prior to writing this piece. I made one of our old albums available for free or pay-what-you-want for 24-hours and casually mentioned it on our social media channels. We sold more copies of it than we had to that point in the same year. People paid between $3 and $15 NZD for a six-song digital album they could otherwise get for free (not just from us!). It reminded me of this tweet:

@decortica this may sound strange, but I value the album a lot more than $2. Is there any way to give you more?

— Steve Dennis (@subcide) August 16, 2010As a musician today, it feels like I spend 10% of my time playing guitar and 90% on “administration.” Freemium and direct-to-fan models are genuinely exciting to me. Any label that can see the opportunity can afford to get excited about it too.

What's been your experience with music distribution models? I'd love to hear about it.

Originally published 2013 on Tumblr.

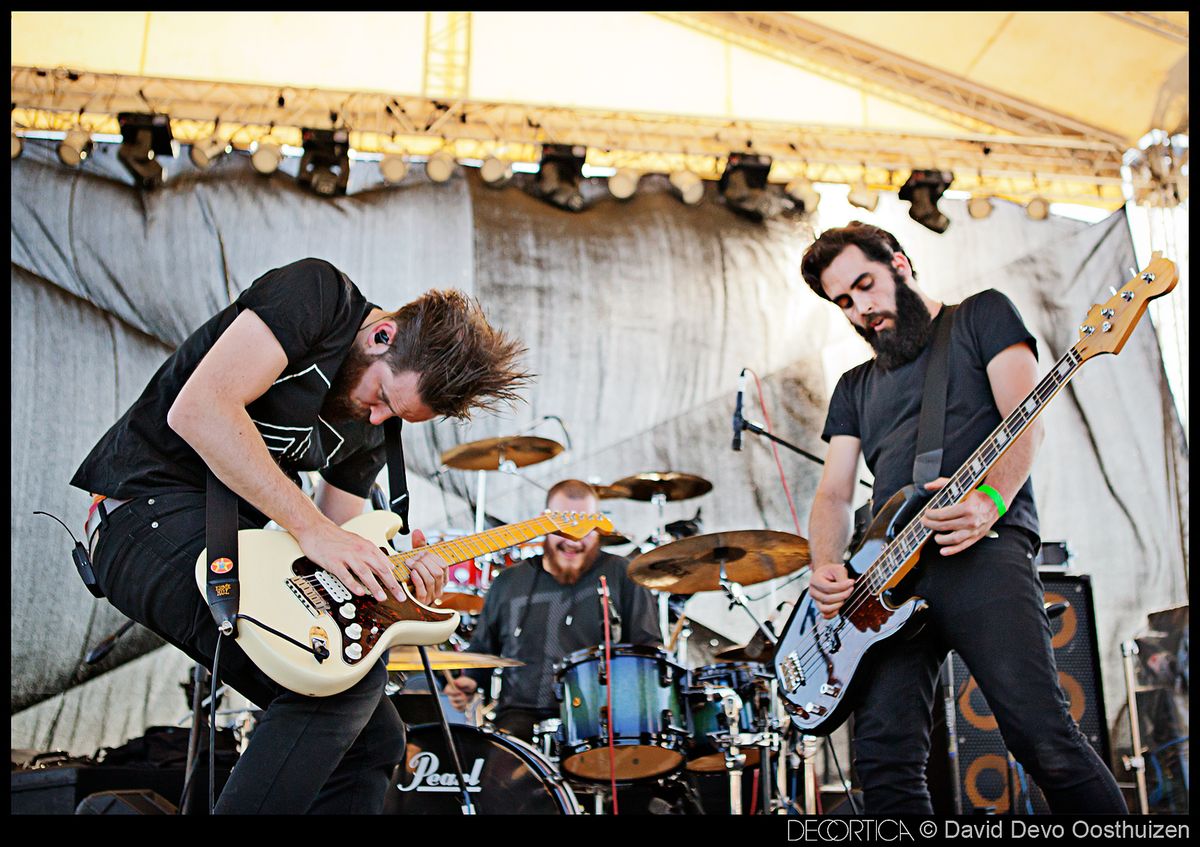

Photo credit: David Devo Oosthuizen